On the Monster in Western Society

The word monster, coming from the Latin root monstrum, meaning a divine omen or a portent, first makes its appearance (to my knowledge) in the written English language in Chaucer’s Monk’s Tale,

“Was neuere wight sith that this world bigan /That slow so manye monstres as dide he”

“Was never such a man since this world began / That slew so many monsters as did he”

In the late 1300s, in the heyday of the Benedictine monk, with his mandated reading and his life in the scriptorium, the illumination of the book became commonplace. Monks would scribe religious scenes, epic battles, and bits and pieces that either illustrated the text or illustrated the moral intention behind the text. Further, monks were talented scribes, often solely responsible for transcribing works whenever the wealthy decided to pay the ungodly cost to own a new book. The illuminations left the monastery and moved into the homes of nobility, the French and Latin speaking Englishmen of the court.

Often, those portents would take the shape of mythical beasts and creatures, primarily Greek, and often owing their shape to an unnatural blending of earthly creatures. The eagle with the lion’s tail and the woman’s head, the serpent of many heads, she with the lion’s body and the head of a goat and a living serpent for a tail. This relates significantly to the impact that Aristotle had on Western thought at the time but would go on to influence western culture to an unusual degree.

These illuminations were beautiful and often used didactically, to illustrate the text and to portent meaning. They were true portents and divine omens, symbols of the wrath of God and whim of Lucifer.

The monster became the mythical creature, the strange, unnatural, the hideous. Not to the common man but to the learned man, e.g., the Latin speaking man. When Chaucer brought Monster to written English, he was transcribing a word that he was most certainly familiar with from Latin.

At around the same time, perhaps in part because of the influence of its false cognate, monstrare (meaning to show) (and which is the root of the word Muster (to show, to sample) (Demonstrate) and behind the Dutch usage of the word Monster to mean sample) the word entered the world of medicine.

By 1400, the first written record of the word Monster was used to refer to a malformed babe, in the Cursor Mundi, a 30,000-line poem that has had more influence on the English language than almost any book except perhaps the Bible or a collected works of Shakespear.

(And this is also interesting, because many people do (falsely) cognate the two together monstrare and monstrum, despite no evidence that I can find of such. Although Chaucer also spoke French. However, the depiction of monster as demonstrative, to reveal and portend, as a specimen, very much feels right – so it would make a significant amount of sense for this (false) cognation to have appealed to man in his past as well as his present and I will touch on that in a minute if you have the patience to continue reading along to me rambling)

If þou fand..A barn..þat had thre fete and handes thre…

Sli scap to se was na ferlik*,

Bot monstres moght man call þam like.

Should you come upon some child with three feet and three hands …

Such a creation would be awe-inspiring to see.

Though mankind shall name him monster

*Please note, I could not find a translation for this handily available on the Internet and was so forced to stoop to make my own. Judge it harshly. My version does not rhyme. Surely you noticed. *what? No one published all 30,000 lines of the Cursor Mundi online in modern English? And I’m too lame to own a copy.

(page 566)

*(Oh, there’s a fun word in context, ferlik. From old Norse, meaning a monster, an abnormality, monstrous – and worked into English to mean something similar to the root Latin word for Monster, a divine omen or a portent something wondrous and terrible to see).

And here it’s important to understand that this is exactly what the “doctors” of the 1400s were trying to say when they spoke of monsters. A portent of doom, a warning of divine wrath, a sign of the devil – the calf has two heads because the farmer’s wife is a witch and God brings his wrath down upon the home. Today, we might think that the monster refers to the Gargoyle because of its appearance, but rather, both were a metaphor for the wrath of God. Not Quasimodo as the grotesque, but the grotesque, the gargoyle, as a mockery of Quasimodo. For only in the absence of God’s light could such horror come to be. (Ugh, religion)

At the same time, the usage of the word “monster’ to mean “deformed” became fairly common. In fact, while the word monster is not cognate/related to monstrare (to demonstrate/sample) it came to be used as such. The monster as a specimen, as a sample, as an example, something unique. Monsters in bottles, a monster born showing no spleen, congenital twins monsters of joined together flesh.

The word monster came further into play in the 16th century as genetics took an interesting turn. People believed, truly believed, that a man could have a child with a mare, and so beget a monster, a man with a horse head. It was common to reference “monsters” as humans bearing the traits of animals, sometimes in extraordinary ways. It wasn’t until the 1800s that men began to firmly believe in heredity, like will always beget like and no gesture of divine power will ever see a true child with a horses head. Though I get ahead of myself, 500 years ahead of myself.

It’s also not nearly so archaic as you might think:

An acardiac acephalic monster following in-utero anti-epileptic drug exposure. _ European Journal Obstetr. & Gynecol. vol. 65 245, 1996

The Monster of Cracow is one of the most famous of the children born of human mothers with animal parts, reportedly born between 1543 and 1547. The child was described as having dogs’ heads on its elbows, chest and knees, the eyes fiery, monkey’s heads for teats, a horn like an elephant’s trunk and …

It was reported to have died just hours after birth, speaking fully formed sentences despite its tender age, “Watch, the Lord Cometh”, a true portent of God’s wrath. This type of depiction grows more common with the rise of Lutheranism, as that religious movement sought a means of denouncing the Catholic Church, and used symbols of monsters, portents of wrath, as signs from God that the Catholic church was corrupt.

It was that same 16th century which began to see the first specimens of animals imported to Europe. Armadillos and walruses were labeled monsters, the pig-turtle and the fish-ox, a mix of two animals known to nature and so monstrous. That tradition of names was maintained in protestant countries – when the platypus (meaning flat-footed duck) was named in the Netherlands it became the bird-face-animal (vogelbekdier). Even the bird of paradise was labelled as a monster. So, the monster had already begun its transformation (as did the word wondrous) away from the terrible and towards the modern interpretation that can be as good or as bad as you wish it to be. See: The Shape of Water.

But that concept that idea of the word monster, which means both portent of doom and beastly or outside of nature comes into play in a viscerally cultural way. The Christians adopted the stories of the little hobs which would steal children away in the night if they did not get their bread and milk – but they also implemented the stories of beast and man and transformed them into something better representative of Christian ideals.

Examples of mankind as beasts abound in Greek literature. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Lucious becoming a donkey, Proteus and his ability to change shape at will, Zeus and his ability to transform into whatever his prey found desirable. It is a rare thing in these stories for transformation to be anything negative and it is only in stories like The Odyssey, when Odysseus’ men are transformed into pigs by Circe and the tragedy of the Medusa where shapeshifting is used as a punishment.

Nothing more strongly depicts the Lutheran/Puritan ideal of the Monster as an unnatural mix of man and beast than Medusa, standing proud before Perseus rids her of her head.

That is not the case in European folklore, where it’s significantly more likely that a man becomes a beast as a result of a transgression. And that carries on into the modern day, if you look at Disney’s reinterpretation of Beauty and the Beast.

Metamorphosis, or the shift from beautiful princess to ugly toad, from rich prince to playful bear, most often makes the hero or heroine less than they were. As (divine) punishment.

Often, in moralistic modern tales, the transformation is about making the outside match the inner person (E.g., Disney’s Beauty and the Beast). Yet, in the older tales, that was not so, and instead, man became beast or frog at the whim of a powerful other, sometimes following a slight and sometimes for no listed reason at all. See my earlier blog on the Enchanted Universe for more on that.

The physical transformation from prince to frog is superficial, and any character or personal growth the frog who is a prince would wish to go through, he must do as a frog. He is man and beast at once, a monster.

This narrative technique is often used to refer to growth:

- The spoiled princess who must grow up

- The ne’er do well (spoiled) prince who must do the same

- The bully who must learn to be kind

In Rapunzel, the protagonist with her monstrous hair, must grow emotionally and choose for herself and take ownership of herself. This is after she is transformed physically with the loss of her hair, socially with her transformation into an unwed and poor mother, and emotionally, with her choice to take the prince to bed.

That’s also present in more modern tales, like with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Here, the protagonist, herself a monster in every description of the word, must learn to empower herself through what makes her human (her voice and her ability to communicate) and not with superficial beauty before she can shed her monstrosity and become truly human. A child growing up, from person in training to a person.

The taming of the shrew.

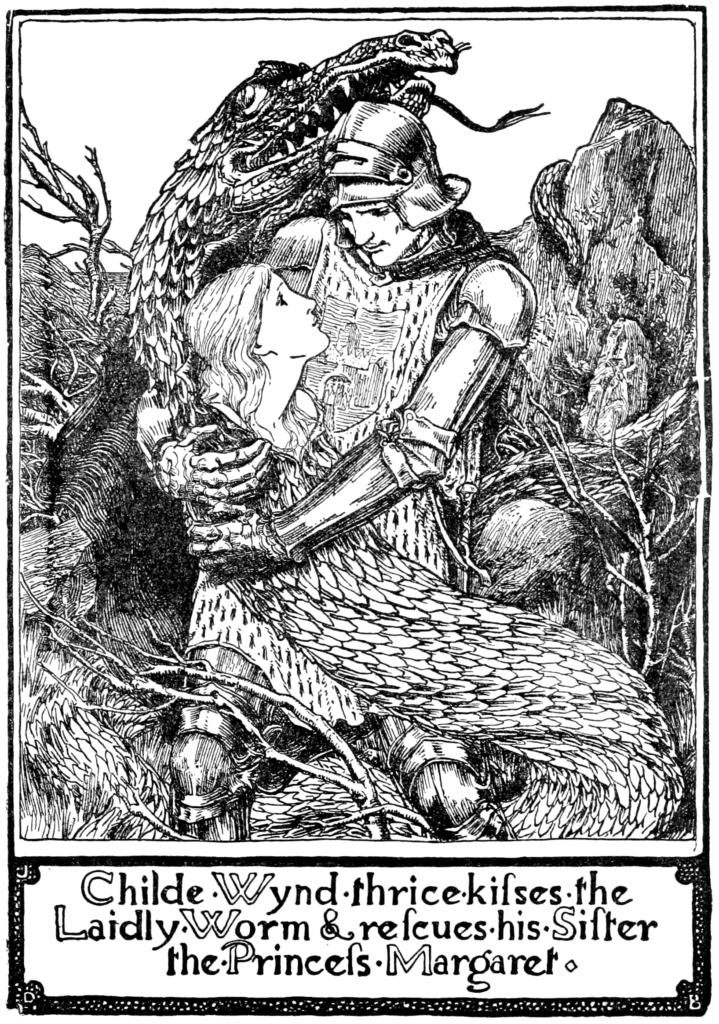

The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh

Men, however, are not typically handed stories about being tamed, although they frequently are depicted as animals which are much more in need of taming (bulls, bears, lions, donkeys).

Men’s stories are also typically:

- The man must free himself from his tormenter, often by killing it

- The man must find redemption (typically in the bed of a woman, rather than by some growth of character)

So, they are still about reaching adulthood. About shedding the monstrous nature of beast and man of childhood and becoming solely a man.

And actually, that makes sense in a historical context, considering the coming of age of men would have linked to marriage. The boy becomes a man through the marriage bed and fathering a child – taking on the responsibility of provision and protection. Fast forward to 1690 and John Locke’s “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding”, and the introduction of the Tabula Rasa. Western society began to believe in the human mind as a blank slate in childhood, a blank slate which must be molded from beast to man.

So, childhood as we know it today, an age of innocence when the child is a separate being, both beast and man, and in need of protection and guidance from the adults around them was born. Children then, not as miniature humans, but as monsters. The perfect protestant foil of a human born into the world in need of salvation from all that it is.

Nowhere is that better defined than in Beaumont’s Snow White & Rose Red, which is often pitched as a Bildungsroman, a coming of age for a young woman who starts out repulsed by man and sex and transforms into a mature woman. Yet, it is the man who is depicted as being less, as being a beast, as being a Person in Training. The prince who must woo a woman despite not yet being a man himself.

In Beaumont’s version, unlike the Disney version where Belle simply gets to be a mother and teacher, Beauty is indeed wooed by her prince – who dines with her nightly and talks to her.

“I am pleased with your kindness, and when I consider that, your deformity scarce appears”

Ah yes, the monster we were looking for, appears.

And alongside him, woman, not as the civilizing force of the later missionary movement that we see in Beauty and the Beast from Disney, but as one who must learn to see around the social ideal and who is being handed a morale to look at inner beauty and worth. To see the child for the man he might become.

That mirrors the bear in Rose Red and Snow White, which shows up to the girls’ door and asks to be let in. At first terrified, the girls end up playing with the bear and befriending him. When he later transforms from a beast, this bear who roughed about as little more than a giant dog, promptly marries one of them as a man, with no questions asked and no talk of getting to know the man – this monster is again a metaphor for a child become a man.

As I was very recently informed by a truly horrible book, the German tradition once referred to children as frauhsce (froggy), an animal and a man at once, a Person in Training and not yet a Man in the sense of the word of Person.

In the Christian mythos, or at least in the European mythos, which was impacted by Christianity and its ideals, man is almost always turned into a beast as a punishment for some transgression. He becomes an abomination unto nature, a monster of man and beast. A portent of (some being’s) wrath.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley also very nicely played into these metaphors, when she chose to use an unnatural creation as an analogy for her inability to love her child. Shelley’s epic is widely agreed to be an exploration of the psychological impact of postpartum depression and coping with grief in unhealthy ways.

Looking at a newborn baby, she felt no motherly love and attachment, only terror and horror at this ugly and beastly thing she had brought into the world.

“How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavored to form?… For this I had deprived myself of rest and health. I had desired it with an ardor that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room…”

Victor Frankenstein

Adam, Victor’s first Man, was an embodiment of that, a creation which was strung together outside of the laws of nature and so abhorred by it. As Adam, Frankenstein’s Monster, lingers in one place, nature departs. A twisting of nature, of bones and parts found and pieced together in slaughterhouses and morgues – a portent of doom and unlovable to the parent who wanted him so badly when he was not yet born and yet was unable to love him in life. A portent of doom. A child. A tabula rasa of blank slate waiting to be molded. Both beast and man. A monster.