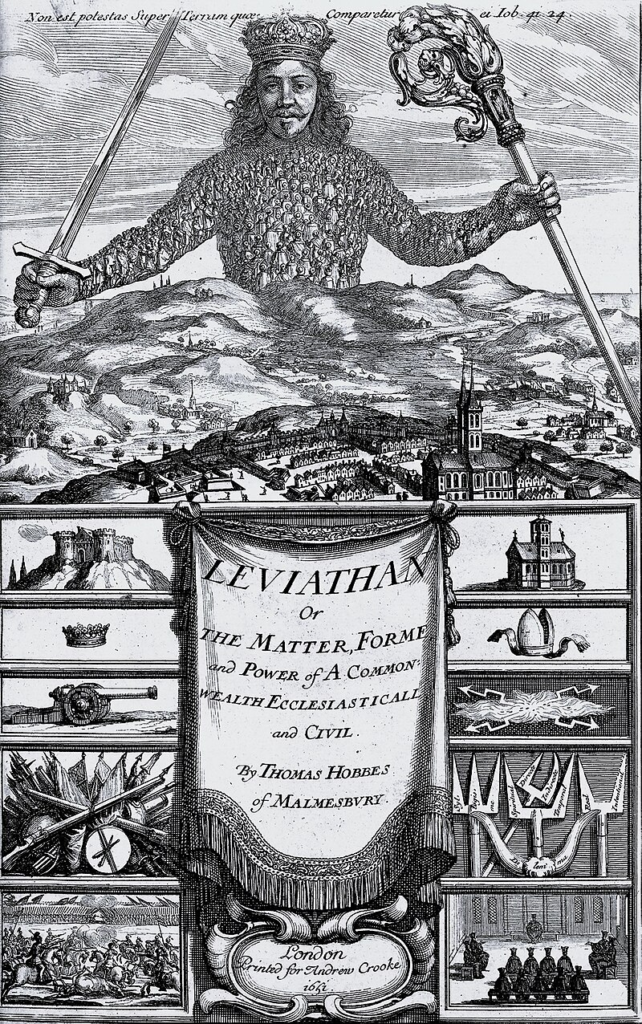

In April of 1651, a 63-year-old white man published a book that would go on to influence the rise and fall of governments, societies, nations. Thomas Hobbe’s Leviathan detailed the theory of the social contract, the idea that in a society, people give up the power of the individual to the whole – meaning that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. That summation of individual rights, and only that summation, could ever provide the grounds for the right to punish someone else – otherwise the individual right to do whatever you want would always come to an even head with the individual right to not be harmed, emotionally, physically, financially.

Hobbe’s work was ultimately flawed. Despite showing a breadth of compassion for humanity and desire to create a society based around kindness and fairness, Hobbes clung to ideals drilled into him by his peers, Christianity, and his education. His book is rife with ideas that now seem inhumane and flawed. At the same time, it resonates strongly with many of the themes of modern politics, revolution, and leftism. Despite the fact that few leftists give it a chance because it is (sic) an authoritarian bible.

Plato and Aristotle believed that the mass of humanity were (to paraphrase) too stupid to ever govern themselves. Instead, an educated elite must be raised with the information and education to guide the unwashed masses to what was good for them. Hobbes’ book rejects this but ultimately recommends the need for a [divine] figurehead, one man imbued with all the power of those beneath him, to act as a central figurehead and fulcrum, a single judge and jury to administer the morality of the people to the people and for the people.

Hobbes was also not someone who necessarily believed in the divine right of the figurehead, rather his career, his livelihood, and even keeping his head heavily depended on him citing arguments for the monarchy and their divine right to rule as well as for the Church.

Which is why the same work contains what feels like contradictions. Hobbes advocates for the elite of a crown, while openly declaring Aristotle, the pride and joy of the western world and all education at the time, to be an [overhyped douchebag too arrogant to see the people in front of his own nose as the intelligent, caring, and capable humans that they were]. A careful reading will show argumentation about the implausibility of religion followed by addendums of “oh, of course not *our good absolutely true Christian religion*”. And, in an argument that will forever endear me to Hobbes, he argues against giving non-people (businesses, churches) rights. He also argues that monopolies by businesses and people can only lead to harm.

But at the heart of it, Hobbes is not arguing for the animal nature of man or for our inability to govern ourselves. Hobbes explicitly uses the first half of the book to state that you cannot expect a person whose primary concerns are whether they eat tomorrow to have the ability to concern themselves with morality and right.

The State as a Tool

Hobbes makes several very cogent and strong arguments that the state only holds value when it can maintain the moral codes demanded by the people. Unless the state is upholding the wishes of the people, the state is no longer part of the social contract and must be eradicated.

In fact:

“For seeing every subject is author of the actions of his sovereign, he punishes another for the actions committed by himself”

Hobbes says in words that the state is responsible for the actions of its people. If the state creates a situation in which someone must commit a crime in order to live [comfortably], the state is responsible for that crime and any punitive action against them is failing them.

He also outlines how a system cannot ask something of someone if that something harms the person being asked. You cannot be asked to take actions that harm the self in a moral society.

And Hobbes argues that your ability to be part of the social contract is incumbent on your ability to understand the social contract. If you do not understand the terms by which you are bound, you cannot be bound. It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that people are educated and that they have the opportunity to understand and be part of the laws by which they are governed.

“Shall whole nations be brought to acquiesce in the great mysteries of the Christian religion, which are above reason; and millions of men be made [to] believe that the same body be in innumerable places, at one and the same time, which is against reason; and shall not men be able, by their teaching, and preaching, protected by the law, to make that received which is so consonant to reason, that any unprejudiced man needs no more to learn it, than to hear it? I conclude therefore that in the instruction of the people in the essential rights [] and consequently it is [the sovereign’s] duty to cause them to be so instructed.”

The Danger of Charisma-Based [Political] Decisions

Hobbes argues that it’s dangerous to allow people to win the sway of popular vote via charisma. That’s an argument from the 1600s, but a quick side-eye at Trump, Reagan, or many other American presidents on record would say that it’s still a contemporary problem. Flash back to 1788 in the United States when the general of the American revolutionary war set a precedent for charisma rather than qualifications winning elections, when George Washington took seat as a figurehead for a new country. That precedent was followed up by presidents such as Ulyssess S. Grant, pride of the American North during the country’s civil war, but a trainwreck of a president who ushered in an era of nepotism and ineptitude in the oval office that has not ended to this day – and was open to the point where nepotism in the Oval Office was known as “Grantism”. Or Reagan who became president on nothing more than a degree in economics, a career in acting and radio broadcasting, and a charismatic approach promising people whatever they wanted so long as they were willing to blame someone else for their problems. Or was that Trump?

The government that allows a populace to remain uneducated and unable to make good political and moral decisions is failing its people and failing the social contract.

And, to Hobbes, the government was responsible for ensuring that people could be fed and housed, not because to Hobbes that was the moral thing to do, but because that ensured those people had the capability to prioritize moral right and law instead of theft and crime to feed and house themselves. Would not people be better equipped to work and leisure if they were assured housing, sustenance, and comfort regardless? I have inherent moral disagreements here because my moral code posits that everyone has the right so a safe, happy, and comfortable life free from stress or concern over those resources to the point where I believe it’s immoral to profit from [things] that contribute to such. But, I’m somewhat of an extremist in those views and many people disagree with me.

That same criticism of the moral right to education and informed consent applies to leftism and any kind of communist good, in that it cannot be moral to push consensus for ideas based on charisma rather than on education and informed adoption of policy.

The Animalistic Nature of Man

Hobbes book defines that without the social contract, men are lawless and have no reason but to look out for themselves. There are obvious things to argue against here of course. But, to Hobbes, without the social contract and government, honor systems prevail, and every man must be responsible for his own justice, in which individual morals prevail. People must band together, agree to a uniform set of moral principles, and instill an authority with the power to uphold those morals.

The social contract exists even without government, yet the government enforces it and gives its people the means to relax their own defense of their rights. And that creates an intrinsically better world.

Hobbes intrinsically denies the ability of the government to be religious, and instead posits that the social contract supplants religion while also going “Please take this in good faith that I actually really, really love the church and stuff”.

“no religious doctrine or practice can be authentic if it does not lead to practical compassion.” (Karen Armstrong, The Battle for God)

Of course, there are many questions regarding the truth in the animalistic nature of man. In whether governments are as tractable as would be desired and don’t instead become their own entities with their own interests. And in whether the people behind them can be kept from corruption, which is why Hobbes argued for a monarchy, because in addition to it helping him to keep his head that argument was based on the fact that a single man is easier to remove from position if he becomes corrupt. (I disagree with the single ruler theory personally).

But still, there are benefits to a predictable and stable government, with its income tied to the wellbeing of the people, and little prone to corruption. Making that a reality in any kind of modern system has failed, although this is by far not a reason to bring monarchism back.

In “The Battle for God” Karen Armstrong charts the nature of the roots and resurgence of fundamentalist religions, tracking them to a fear of losing meaning, morality, conviction – and being left both without the imposed morality of a strong social contract or a strong religion, opted for the latter.

“Fundamentalist faith was rooted in deep fear and anxiety that could not be assuaged by a purely rational argument. [] The moral and spiritual imperatives of religion are important for humanity and should not be relegated unthinkingly to the scrap heap of history in the interests of an unfettered rationalism.” (Karen Armstrong)

Still our own governments could greatly benefit from taking some of those fears to heart and for example, formalizing political education with mandatory education requirements before elections, tying political salaries to the wellbeing of its poorest people, and banning advertisement and marketing techniques for politicians. In short, taking elections out of the hands or charisma and into the hands of informed (but still emotional) decision-making.

Do People Know What They Want?

Market philosophy suggests that the public will work as a quality filter, sorting what’s good from the chaff. Market demand means that people will spend their money in a way that reflects quality. In practice, that’s virtually never what happens.

Take the much-touted popularity of works like Dan Brown’s novels, objectively some of the bestselling books of our modern times and yet objectively mediocre in every way.

Take Freakonomics, which pointed out that in 2012 the film The Avengers grossed $200 million more than the next biggest film at the box office, yet the sub-par performing Argo won the Oscar and was cited as the best film. Were the experts wrong that Avengers was the best film?

No. Although it is questionable that Argo was the best film either, considering the subjectivity of the matter and the mediocrity of the film in question.

But, does some “smartypants” know better than the ticket buyer?

The ticket buyer isn’t looking for “Good” they are looking for “entertaining” and “accessibility”. They’re tired and overworked and just want to relax and not have to think.

Many, including authors like Michael Sandel pitch this as a world gone mad, a system that changes values for the worst – because people spend not just on what’s good and best for their money but also what’s accessible, entertaining, and easy.

That’s why hard hitting and emotionally tolling films are rarely films that people come back to time and time again.

Take the 1999 cult classic, The Mummy starring Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz. It’s a hodgepodge of tropes haphazardly mashed together and bastardizing the film it was based on, whilst pandering to western machoism, European elitism, and riot girrrl feminist sensibilities all at the same time – a useless bit of frippery that has somehow worked its way into the hearts of millions including mine. It’s a wild ride of *bad* media that is enjoyable providing you’re willing to shut up and enjoy it for what it is – mindless entertainment.

Indirect network effects mean that once someone you know sees a thing and enjoys it, your likelihood of seeing the same thing are the same. People want things that are accessible, they want an easy bar, they are tired because re Hobbes in 1651, the man who is caught up in ensuring that he has the means for sustenance does not also have the means for subjectivity.

Without first freeing mankind from the burden of fear of sustenance and stability, once could not ever rationally expect the average person to have the time, motivation, or resources to invest in the resources to figure out what’s good, why, and what the results should be. Pacifism is theatre, staged for those with the privilege of an audience, but so is informed decision-making and deep-dives into political theory.

Do the Educated Know What’s Better?

Policy assessment assumes value judgement in selection, but that’s often simply not the case.

That’s also why economists and governments have recoiled in horror from the “unexpected consequences” of bills and policies. E.g., in British Colonial India, in an effort to reduce the population of cobras in Delhi, the government issued a reward for dead cobras. Local citizens started breeding cobras for the reward. Realizing the situation, policymakers cancelled the reward – and citizens released their bred cobras, worsening the original issue.

Or Mexico City, which instituted a ban on driving every day per week, tracked by license plates on cars. The hope was to reduce air pollution. Drivers, instead of abstaining from driving one day per week, bought a cheap second car, often with higher emissions problems, to get around the ban and resulting fines.

The theory of individual choices failing to contribute to the social good as directed by a government is also a well-documented one in philosophy. Marx, in an 1867 work which I don’t have to name, shared a theory of economic crisis of capitalists saving money by laying off workers – eventually reducing demand for the output of capitalism until the system fails by lack of profit – which interestingly looks remarkably similar to arguments against AI and automation under capitalism today.

And that’s been pretty consistent throughout modern history. Take this quote from The Great Dictator (1947) by Charlie Chaplin:

“More than machinery, we need humanity; more than cleverness, we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost…. You, the people have the power – the power to create machines. The power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure.”

Keynes, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money” discusses how citizens meaning to be good can also create downturns by being overly thrifty. Capitalism tells people to save money and not buy avocado toast – but when people stop buying the toast, the restaurants go under, the restaurant owners stop buying supplies, the suppliers go bankrupt and …

And, that’s a concept that’s led many, including myself, to believe that it’s simply not ethical to impose an existence on someone else without first offering education, choices, and informed consent. An argument that was put forth by Hobbes, supposed champion of the authoritarian, in 1651.

In “Speaking of Universities” Stefan Collini argues that the concept of free time is a concept of the elite. People with health, wealth, and free time to have hobbies, interests, pursuits. Everyone else “just watches TV” and “plays games” (these are hobbies, in my opinion, one form of media is not better than another).

That view is ultimately elitist, supremacy guised in concern, but again, back to Hobbes, “if a man is concerned with survival, how can he…”