Most of us have, by dint of a slip of the tongue or while over explaining something or other, managed to say something that ended up being ridiculously repetitive or tautological. Think of phrases like “fortified fort“. You say it, take a second, and realize how unbearably stupid you sound. It’s okay, everyone does it from time to time. It’s not even stupid, it’s just your brain making connections between words and you saying them aloud, an example of the human brain at its finest – albeit that’s not how it makes you feel if you’re the type to notice these kinds of things.

But, a closer look at language of any kind shows that people make these kinds of repetitions constantly, consistently, and in both historic and modern times. Take RAS Syndrome, itself a perfect example of the phenomenon to which it refers.

RAS

Redundant Acronym Syndrome Syndrome or RAS Syndrome is the process of saying one or more words from an acronym along with the acronym.

ATM, Covid, DC Comics, ISBN, VIN, and many other acronyms are all victims. For most of us, it’s so normalized that you probably don’t bat an eye going “DC Comics (Detective Comics Comics), ATM Machine (Automated teller machine machine), or SSD Drive (Solid state drive drive).

Of course, if you were to say them aloud, they sound silly. You’d never use a RAS without an acronym would you? Of course not! Or would you?

But the human love of repetition doesn’t stop there, not even close.

Cross language tautology

What do Chai tea, Pita bread, Naan bread, Bapao bun, Please R.S.V.P., global pandemic, and Roti bread have in common? They’re all cross language tautologies, where a language foreign to English introduces a word (usually food or landmarks, but in the case of the French “Please respond”), and English repeats the word. Chai means tea, your chai tea is “tea tea”, and there are three instances of “bread bread” in this list.

Nowhere is this phenomenon more obvious than in place names, with the River Avon, Hatchie River, River Humber, and many others translating to “River River”. It gets even worse when you consider that there are 6 examples of river names translating to “Big River River” (for example, the Rio Grande River, Mississippi River, and the River Avonmore) and three meaning “Small River River”.

One of the most famous examples of this particular bit of sounding stupid to people who know more languages than you is “Torpenhow Hill”, presumably located in Cumbria England. In the story, Torr is “Hill” in Old English, Penn is hill from Old Welsh, and Haugr (translated to how) means hill in old Norse. The literal translation of the name is “Hill-Hill-Hill Hill”, but it was invented as an example of the phenomenon and referenced to since about 1904. It’s a myth someone made up to get to point and laugh at people about. Instead, the name Torpenhow probably mixes the British Torp/torpen (a small farm) with hoh (heel) to potentially refer to the early settlement and church, which were situated on the curve of a low hill.

But that introduction of new words from different languages, and the way those words sometimes change in meaning, is one of the reasons why we have so many words that mean exactly the same thing.

On monstrous serpents

What do dragons, wyverns, basilisks, drakes, hydra, and wyrms have in common? Not only do people struggle not to use many of the terms interchangeably, they all come from the same root, “Serpent” or “Viper”. While there’s something to be said about the influence of the Christian bible and the great serpent of that story having significant impact on Western culture, it’s notable that many of these words predate the popularization of that particular mythology.

Even leviathan, now more familiar to many as a form of government than a great monster, comes from a root that means “To twist, wind, or coil”

Today, these words are often used interchangeably, to the point where you can find books referring to the same beast as a drake, a wyrm, and a dragon in the same paragraph. But, that’s often been the case, although, historically, serpent has been used as well.

Soda (,) pop and fizzy drinks

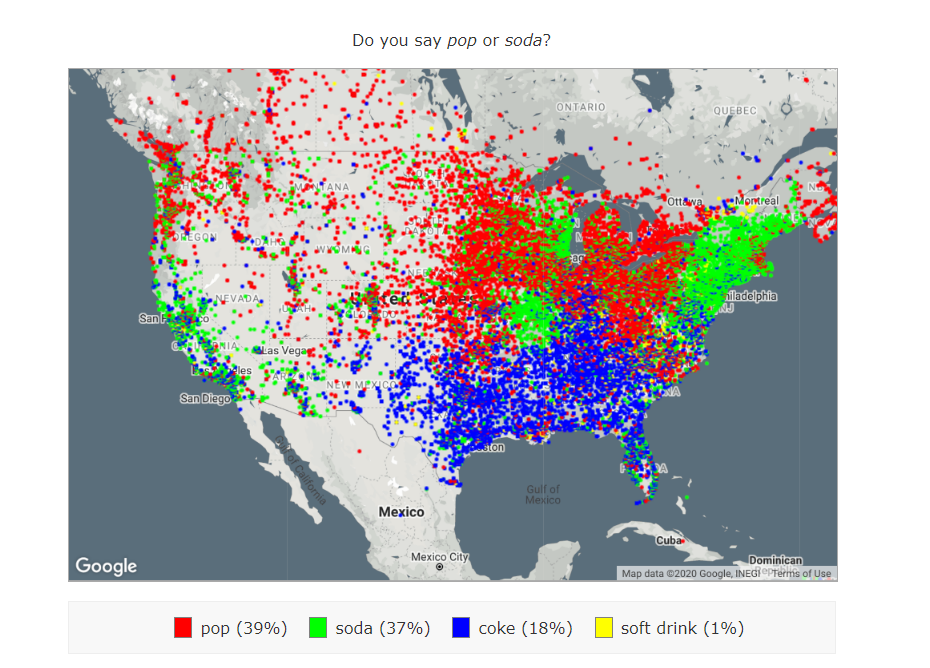

In the late 1700s, Joseph Priestly invented a method of infusing carbon dioxide into liquid, creating a fizzy effect. This “carbonated” beverage quickly caught on, first as medicine and then as drinks more similar to the soda we know today. By 1809, ginger beer was already sold with carbonation. While it contained many different ingredients, carbonated beverages caught on everywhere. But what was it sold as? That depended on the region. Pop, cool drink, fizzy drink, soda, soda pop, carbonated drink, fizzy juice, seltzer, lolly water, mineral, lemonade, and tonic are all terms still used today. Following the mass-market popularity of Coca Cola, the terms cola and coke can both be used interchangeably for “any carbonated drink”.

Why so many names? Carbonated beverages spread in popularity in the early 1800s, before the availability of national media. People were relatively isolated, dialect differences between regions were extremely common, and many areas developed their own words for the beverage.

This kind of geographical drift is why you can both cut the grass or mow the lawn. It’s why most of the world calls a milkshake a milkshake but a small percentage of people living in Maine in the United States call it a frappe. And why highway, freeway, parkway, expressway, throughway, and turnpike all mean (about) the same thing although there are some arguments to be made about freeways not having tolls depending on who you ask.

The great leveler

The reason you know all of those words is international media. First national radio, then international radio, and then finally, the great homogenizing effect of the Internet, famously called “the great leveler” by linguists studying the English language brought these word and dialects together. Modern speakers are more and more often thrown together, mixing dialects, and erasing them. Our need for different words to refer to the same things is vanishing – but we have them anyway, as a relic of a not so far way time when geographic distance meant language drift.

What does that have to do with tautology? Quite a lot, since it often means you have words that mean similar or the same things and you categorize them as meaning the same thing. So, when you go to say a word and say two that mean the same thing, you’re just pulling from categories. Like the thing your mother does of creating Schrodinger’s frankensibling by saying every child’s name – and both everyone and no one is in trouble until the final name is spoken – you’re pulling from categories in real time, and obviously, sometimes that’s going to jumble and turn into tea tea and bread bread at your picnic by the Big River River.